Children thrive when they feel empowered to make decisions. Allowing them to make their own choices fosters independence, builds confidence, and encourages critical thinking. This autonomy-supportive approach not only strengthens their emotional well-being but also plays a key role in their cognitive development. Let’s explore how giving your child the freedom to make choices can unlock their full potential.

Why Autonomy Matters for Cognitive Growth

Autonomy doesn’t mean letting kids do whatever they want—it’s about creating an environment where they can make decisions within safe and structured boundaries. This approach benefits their cognitive development in several ways:

-

Encourages Problem-Solving Skills

Making choices requires kids to weigh options and think critically about possible outcomes. This strengthens their decision-making abilities and helps them tackle challenges independently. -

Boosts Confidence and Motivation

When children feel in control, they develop self-confidence and are more likely to take initiative in other areas of life. -

Fosters Responsibility

Autonomy teaches children to take ownership of their decisions and understand the consequences of their actions.

How to Support Your Child’s Autonomy

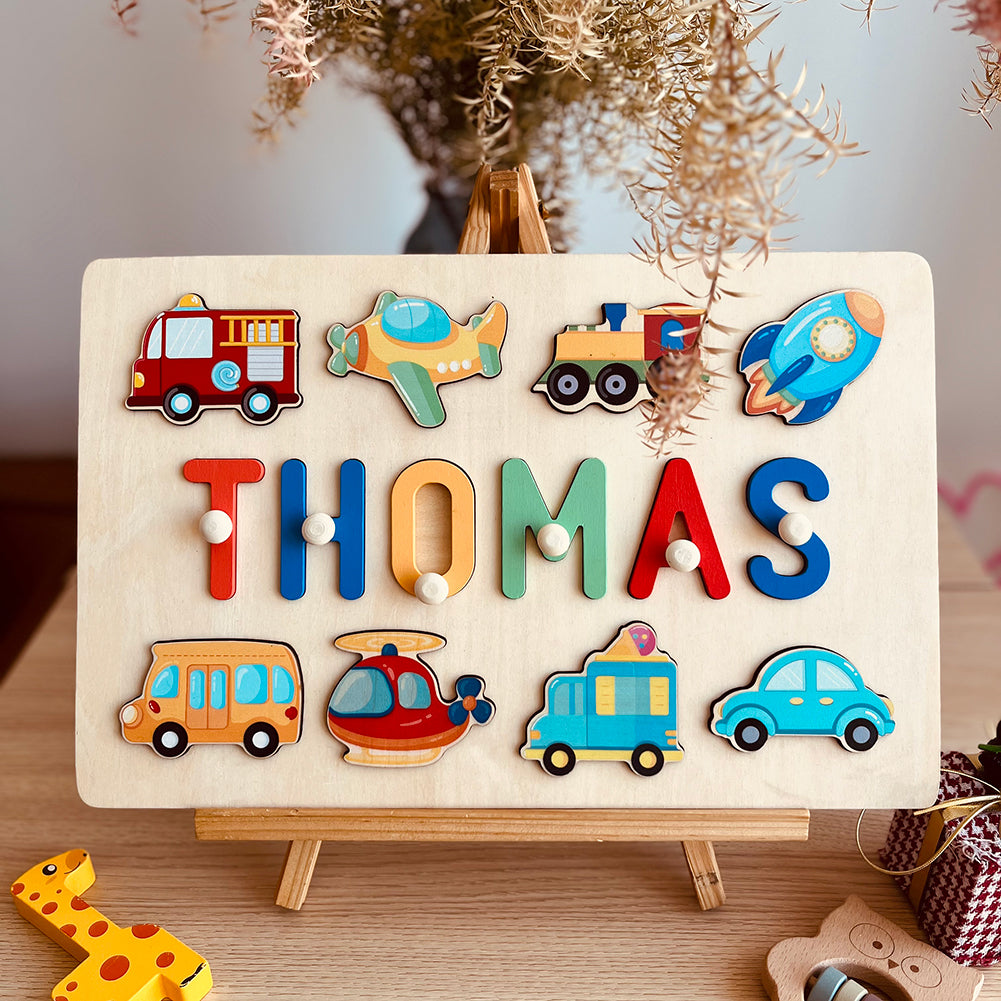

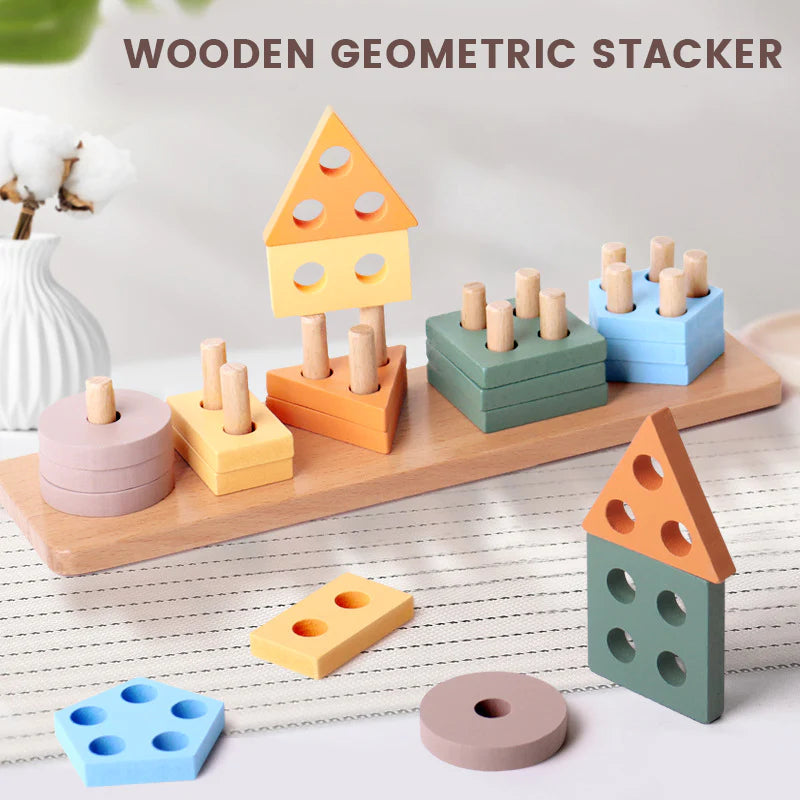

1. Offer Choices That Are Age-Appropriate

Start small! For younger children, offer simple choices like:

- “Do you want the blue cup or the red one?”

- “Would you like to read a story or play with blocks?”

As they grow older, expand the complexity of the choices to include things like:

- “Do you want to do your homework before or after dinner?”

- “Which extracurricular activity would you like to try this semester?”

2. Create a Safe Environment for Decision-Making

Allow your child to experiment with choices in a low-stakes setting. If the decision doesn’t work out as planned, treat it as a learning opportunity.

Example:

If your child insists on wearing a light jacket on a chilly day, let them experience the natural consequence. Later, you can discuss the importance of dressing appropriately for the weather.

3. Set Boundaries While Offering Freedom

Autonomy doesn’t mean a free-for-all. It’s important to set clear boundaries while giving your child the freedom to make decisions within those limits.

Example:

For snack time, you might say:

- “You can choose a fruit or a yogurt. Which one would you like?”

This approach ensures they feel empowered while still maintaining a healthy routine.

4. Respect Their Opinions and Preferences

Kids often have strong opinions, even if they don’t align with yours. Listening to their perspective shows respect and helps them feel valued.

Example:

If they dislike broccoli, involve them in choosing an alternative vegetable to try. This collaboration reinforces the idea that their input matters.

5. Encourage Reflection on Decisions

Help your child think critically about the choices they’ve made and their outcomes. Ask open-ended questions to guide their reflection.

Example:

- “How did it feel to finish your homework early? Do you think it helped you enjoy the rest of the evening?”

This process strengthens their ability to evaluate future decisions.

6. Be a Role Model

Children learn by watching. Demonstrate good decision-making in your daily life and talk through your thought process when appropriate.

Example:

- “I’m choosing to go for a walk instead of watching TV because it helps me feel energized.”

The Cognitive Benefits of Autonomy

-

Improved Executive Function

Executive function skills, like planning, memory, and self-control, are enhanced when children are encouraged to make their own decisions. -

Increased Creativity

Autonomy fosters a sense of curiosity and encourages kids to explore new ideas, boosting their creative thinking. -

Better Emotional Regulation

Decision-making gives kids a sense of control, which can help them manage their emotions more effectively. -

Lifelong Problem-Solving Skills

Learning to navigate choices early on builds a foundation for handling complex decisions as they grow.

Overcoming Common Challenges

-

“What if my child makes the wrong choice?”

Mistakes are valuable learning experiences. Support your child in understanding what went wrong and guide them toward better decisions next time. -

“My child refuses to choose!”

If your child hesitates, offer gentle guidance or limit the options to two or three choices. Too many options can feel overwhelming. -

“They only choose what’s easy or fun.”

Encourage them to consider the long-term benefits of their decisions. For instance, discuss how practicing piano now leads to playing their favorite songs later.

Final Thoughts

Supporting your child’s autonomy isn’t about giving them complete control—it’s about helping them grow into confident, independent thinkers. By allowing them to make choices and learn from the outcomes, you’re fostering cognitive development, emotional resilience, and a sense of responsibility.

Remember, every decision—big or small—is an opportunity for growth. So, whether they’re choosing their outfit for the day or deciding on a new hobby, celebrate their efforts and enjoy watching them bloom into capable, thoughtful individuals. 💕

What choices have you let your child make recently? Share your experiences in the comments below!

Leave a comment